Medicine Hat Potteries (Yuill’s Company)

(A Division of Alberta Clay Products Company Limited)

Hop Yuill from the windows of the family business, Alberta Clay Products Company, watched while Medalta struggled through the thirties. With a little persuasion from Walter Armstrong who was still Medalta’s general manager, Yuill commenced building one of the most modern pottery factories in Canada. Alberta Clay Products was doing well in spite of the Depression, and the company had money to invest in the new venture. He could build “a state of the art” pottery, unlike the Medalta plant which seemed to be a hodgepodge of buildings and work-areas thrown together without any real plan. Of course, Yuill also knew that he would have skilled men to run the plant. It was not very hard to steal Medalta’s best men with the promise of better working conditions and, of course, higher wages.

One can almost feel sorry for Medalta, losing most of its best-trained people to the new pottery. I say almost as perhaps Medalta brought it upon themselves. They had become too distant from the daily operation of the plant. Medalta’s head office was in Calgary, and instead of giving the plant’s managers the freedom to call the shots, they were dictating to them from Calgary. When you peruse the Medalta papers at the Provincial Archives in Edmonton, you can feel the frustration of the local staff. Orders were to be placed through the head office which would pass them along to the factory, often leaving out critical information such as size, colour or the agreed price. It is little wonder that Armstrong and Baumler left Medalta to join Yuill’s Medicine Hat Potteries.

Late in 1938, Yuill’s new pottery was in business. Its main kiln, a tunnel kiln, was placed almost in the center of the factory. The track within the firing chamber ran in a circle about seventy-five feet across and was some 235 feet from one end to the other. The wares stacked in saggars were loaded on kiln cars that ever so slowly moved through the kiln in a cycle that took up to forty hours from start to finish. It only required one man sitting at the controls to monitor the temperatures within the kiln as the pottery moved from the pre-heating, to the firing and finally the cooling stages. Unlike Medalta’s kilns which had to be constantly monitored, the tunnel kiln effectively ran itself.

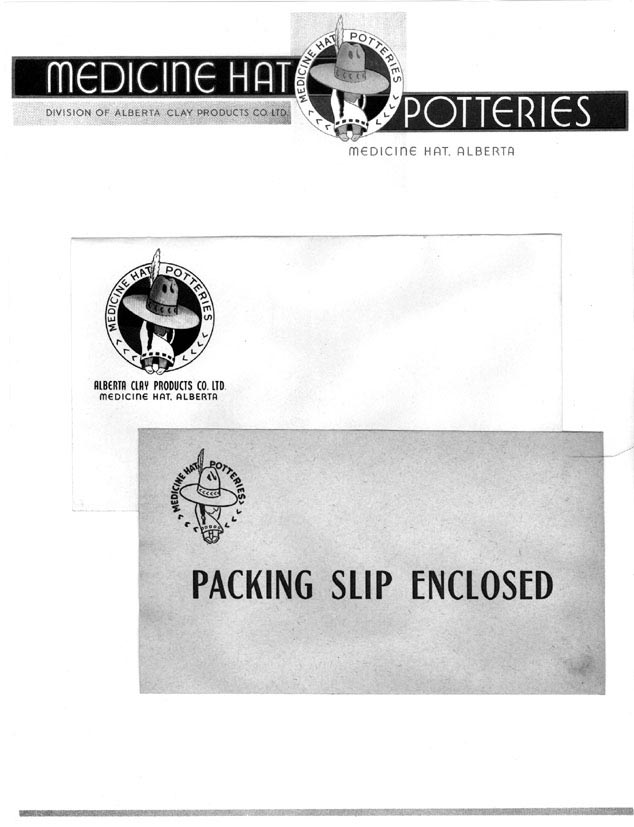

Medicine Hat Potteries quickly designed an attractive trademark. They came up with their “Little Chief” or what some collectors today refer to as the “Sleepy Indian”. The name of the company was arced above the central figure of an Indian. He had a blanket wrapped around his shoulders and was all but hidden by his large sombrero-style hat. The trademark was prominently displayed on the sides of stonewares and the bottom of other products. In time, it was to become as well recognized as the Medalta name.

The salesmen for Medicine Hat Potteries were taking orders faster than the plant could fill them. For a while, they had to acquire some products from Medalta to fill the incoming orders. A few collectors have been lucky enough to find a butter crock with the Medalta name on the bottom and the “Little Chief” stamp on the side. Relations between the two companies were strained at times, but for the most part, they got along fairly well. At the start, Medicine Hat Potteries was not able to make the large fifty-gallon crock, so they asked Medalta to make that size for them, getting Medalta to place the “Little Chief” stamp on the side. Medalta filled their order, perhaps reluctantly, but later they were the ones to ask for favours. One time when Medalta was short of the wooden dashers for a butter churn order, they acquired what was needed from the competition in order for the shipment to be complete.

In time, Medicine Hat Potteries’ stonewares included a full line of crocks from 1/4 through to the 50-gallon sizes, butter crocks, pickle jars, shouldered jugs from 1/4 to 5 gallons in size, several sizes of butter churns, an ice-water cooler jar, a “pig” or bed warmer, a spittoon, acid pitcher, chicken fountain, florist jar, several sizes of bean pots, and jam or honey jars. While their line of products was diverse, almost as broad as Medalta’s, one gets the feeling that they were never as popular. From a collector’s standpoint, it is much easier to find a Medalta piece than a “Little Chief” one. For example, I have seen well over fifty Medalta pigs but only three Medicine Hat ones, and the proportion is about the same for chicken fountains and many other products.

While Phillipson was developing Medalta’s hotel china line, Baumler was designing a semi-porcelain dinnerware set for the Medicine Hat Potteries. The pattern was similar to Medalta’s first set of dishes specifically made for domestic use, but the decoration of encircling ridges and grooves was far more pronounced. The pattern was called “Hatina” ware and it was sold in sets of up to 43 pieces.

MEDICINE HAT POTTERIES HATINA WARE

6 lunch plates 6 bread & butter plates 6 cereals 6 cups 6 saucers 6 egg cups 1 covered sugar bowl 1 covered marmalade jar 1 cream pitcher 1 salt & pepper

One ad proclaimed:

“Colorful - smooth - practical! Smart new ware from Medicine Hat Pottery - you’ll like the good colors of bright red, blue, ivory, green, yellow, light blue ... the silky smooth finish”4

Judging by the number of pieces that are preserved in collections, it was quite popular into the early 1940s and then, once again, after the war when it was re-introduced.

The war brought major changes in the plant’s production. From 1941 to the end of World War II, both Medalta and Medicine Hat Potteries were conscripted into producing china for the Canadian armed forces. The wares from Yuill’s plant were plain white with absolutely no decoration whatsoever. In addition, the plates were fairly thick, made to stand up to the hard everyday use to which they were subjected in army bases all across Canada.

After the war, the Medicine Hat Potteries quickly geared up for peacetime production. Malcolm McArthur who had joined the pottery a few years earlier as their cost accountant, took over as general manager when Karl Baumler left. Mac, as he was more commonly known, was to have a long association with the pottery industry, both as manager for others and as the owner of his own company.

One of the most attractive patterns introduced by the Medicine Hat Potteries was designed under Mac’s direction. It came out after the war and was called the “Canadiana” series. White plates through to salad bowls were decorated with scenes from the prairies and northern Canada including a moose, trout, mounted policeman, oil derrick and grain elevator. Smaller items such as cups and saucers were embellished with green maple leaves. Some Canadiana plates were used to commemorate anniversaries and other special events. One such plate was the one made for the Edmonton Chamber of Commerce in 1953.

A second very attractive pattern had beavers and maple leaves raised around the border of the plates. The border was usually finished with a honey-coloured glaze while the center was a plain white. Quite often the larger 9-inch plate was used as an advertising premium, with the merchant’s name and town prominently displayed in the center. Pieces from merchants in Coutts, Champion and Grassy Lake have all been found. Some dealers are now asking $50.00 to $100.00 for these relatively scarce advertising plates.

While the Medicine Hat Potteries was into the souvenir, commemorative and advertising markets, they were never as successful as Medalta. You can find the names of stores and other firms on ashtrays, mixing bowls, platters, plates, and cream pitchers, but they are relatively hard to find. Medalta made advertising items for more than 500 stores and hotels, but the Medicine Hat Potteries’ items are presently fewer than a hundred in number. In spite of their scarcity, they do not as a rule command the price of Medalta items. Most can be obtained in the $40.00 to $80.00 range but a few can be still be found for around $20.00.

It is interesting to note that some merchants were ordering advertising premiums from both Medalta and Medicine Hat Potteries. One example of this was the stoneware head-cheese bowls and cups ordered by the Montreal area merchants Art Beaudin and J.B. Labrecque. Medalta was filling their orders as early as 1925 and had a long history of dealing with each of them, but eventually, Medicine Hat Potteries captured their business. Did Medicine Hat Potteries undercut Medalta’s price, or was it simply a matter of switching companies when Medalta closed? I believe it was the former, but definitive proof has yet to be found. Other examples of this competitiveness include mixing bowls that advertise both the merchant and Ogilvie’s products and dishes made for The Banff School of Fine Arts. The one example which suggests that Medalta’s price was being undercut was a pair of ashtrays commemorating reunions for Medicine Hat’s own 175th Battalion. Medalta’s ashtray dated to 1938 while the Medicine Hat Potteries’ one dated to 1951. If not for the price, why did they switch companies?

Items for home use were not overlooked by Yuill’s company. Over its lifetime, Medicine Hat Potteries made several styles of mixing and pudding bowls (each available in four or more sizes), candy bowls, chili bowls, three sizes of teapots, a trivet, a pie plate, a coffee pot, a set of refrigerator jars, a ribbed casserole, beer steins, an ice water pitcher with matching tumblers, four styles of pitchers (each in four sizes), jam jars and even a dog dish. One tea set comprised of a cream jug, sugar bowl and teapot—brought out in the early 1950s—looked so awkward that you just had to have it for your home. The only way it can be described is that it was lopsided, as one side was quite a bit higher than the other.

The pottery also went head to head with Medalta in producing artwares. One rather unique vase, designed by Jack Fuller, was a horn mounted on the hoof of a buffalo. While it looked a bit awkward, the flowers actually filled the hollow horn quite nicely. Several Medicine Hat Pottery vases were cylindrical in shape, one with an attractive rose pattern; others were a stepped design, sometimes embellished with small floral patterns. Several of its wall vases were leaf-shaped; others were stepped or cylindrical. In total, they made over four different wall vases and at least six different mantle ones. In addition, they also made bulb bowls, glazed flower pots, and three or more different styles of lamp bases.

Someone on staff enjoyed designing animal-shaped planters. Their attractive line included a standing elephant, another upright on its hind legs, a dog, a monkey, and a leaping rabbit. They even made a number of distinctively shaped ashtrays: a saddle, a sleeping deer, an airplane, and for the golfer, a round one with a white ball in the center.

Decorative plates for hanging on your kitchen or dining room wall were available as well. The series called “Chinook” was given a separate trademark incorporating the “Little Chief” figure. The colourful lithograph scenes were placed in the center of a large 10-inch plate or 13 1/2 inch platter which had a scalloped-style edge. Sometimes the rims were plain; other times they had leaf-like patterns in gold on a green or royal blue background. The scenes included quite a number of birds such as a mallard taking flight from a pond, a group of four ducks gliding into a pond, geese in flight, a flushed ring-necked pheasant or a grouse.

Animals were another favoured topic. A deer with suckling fawn, a bear and cub stealing some honey, a charging grizzly, a moose, a ram and an antelope were some of the patterns. There was even a scene of a bear looking longingly at a rainbow trout leaping in the center of the stream. A rancher could select from a rider roping a calf for branding, a horse’s head, or a pastoral scene of a flock of geese flying overgrazing cattle. If you worked in the “oil patch” you could pick the plate showing a derrick; or, if you were a policeman, the one of a mountie looking out across the valley. Today, any one of these plates is highly collectible and priced in the $60 to $100 range.

The main advantage that the Medicine Hat Potteries had over Medalta in the early years was its modern equipment and of course its tunnel kiln. Yuill’s company was capable of producing up to 350,000 per month, a staggering number if you stop to think about it. It is unlikely that they ever achieved full production as the market just was not there, at least not for what it cost the company to produce the pieces. They were never able to successfully compete with the long-established European firms or the cheap labour costs of the Asian companies. But try they did.

The Medicine Hat Potteries introduced quite a variety of patterns, trying to capture the interest of the Canadian homemaker. Their “Hatina” ware, or ridged pattern as it is sometimes called, was replaced by their “Matina” ware. This new pattern in brighter colours had an attractive raised spiral flute design around the border. It was followed by plainer patterns with no raised or grooved design, made attractive by a wide selection of lithograph decorations and catchy pattern names. Calico, Rustic, Lazy Daisy and Chop Sticks were some of the regular patterns; and, of course, if you owned a restaurant, you could pick your own design and have the restaurant’s name placed on it. Several ranchers took advantage of getting personalized dishes. The set decorated with a bull showing the flying W brand was a Christmas gift in 1954 to Wally Wells from a neighbouring rancher, George Murray, who had obtained his own personalized set the year before.

But in spite of all their hard work and the diversity of their wares, the Medicine Hat Potteries just could not make a success of it. All good things must eventually come to an end, and finally, in 1955 the Yuill family decided to sell out. The sale of his hobby came as a great surprise to Hop Yuill, for without his knowledge, the family had sold the plant to Marwell Construction of Vancouver. But, at least, he still had his Alberta Potteries plant at Redcliff.

Copyright rongetty.com, All Rights Reserved

Login - 216.73.216.144